Are young voters really relevant or key to winning?

The government, political parties and civil societies have to think of creative ways to encourage, educate and mobilise more young voters under 30 to come out and vote.

Just In

The recently concluded Johor state election last Saturday (March 12) has only served to confirm that mainstream coalitions such as Barisan Nasional (BN), Perikatan Nasional (PN) and Pakatan Harapan (PH) are still the dominant players on the scene. That said, budding new entrant Muda managed to win one state seat with the help of PH.

Muda secretary-general Amira Aisya Abd Aziz, 27, won the Puteri Wangsa state seat with a majority of 7,114 votes in a six-cornered fight. She defeated BN’s Ng Yew Aik, Pejuang’s Khairil Anwar Razali, PN’s Loh Kah Yong, Parti Bangsa Malaysia’s (PBM) Steven Choong Shiau Yoon and independent Adzrin Adam.

However, Muda did not manage to win the remaining six seats contested.

Therefore, whether both the voters from the 21-29 age group and the new bloc of voters from the 18-20 (so-called Undi 18) age group will play a critical role in subsequent elections – or hold the key to decisive electoral victory – remains to be seen.

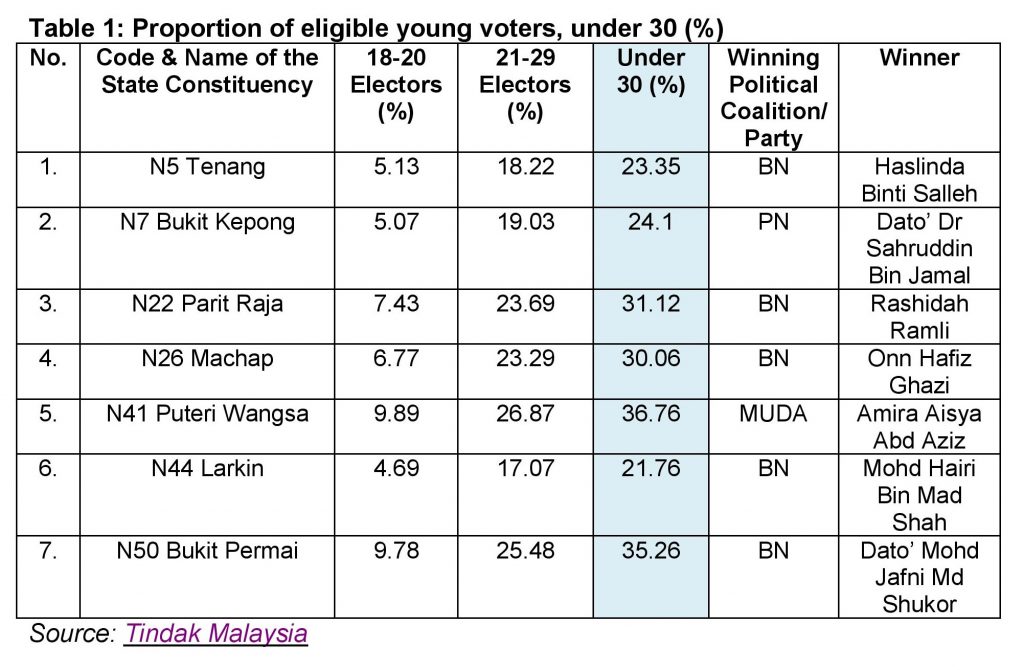

Let us look at the proportion of young voters under the seven seats contested by Muda in Table 1:

Of the remaining six seats contested by Muda, BN won five and PN one. Despite Parit Raja, Machap and Bukit Permai having over 30% of Johorean voters under 30, BN secured all three state seats comfortably.

Let us also look at the other state constituencies with over 30% of Johorean voters under 30 in Table 2:

When combining Table 1 and Table 2 to analyse how Muda as a youth-based political party and main coalitions such as BN, PN and PH performed, BN secured 13 out of 18 state seats with over 30% of young voters under 30, followed by PH with three. PN and Muda each secured one state seat.

Nevertheless, let us further analyse state seats with over 30% of young voters under 30 based on the Malay, Chinese and Indian ethnic classifications in Table 3.

Of these 15 state seats with over 30% of young voters under 30, BN secured 11 seats, followed by PH with three and Muda with one.

State seats such as Kemelah, Bukit Pasir, Parit Yaani, Parti Raja, Machap, Panti, Pasir Raja, Tiram, Permas, Kota Iskandar and Bukit Permai with over 50% of Malay population and less than 45% of Chinese and Indian population were secured by BN. On the other hand, PH managed to win urban state seats such as Simpang Jeram and Johor Jaya with similar ethnic group compositions.

The urban-rural divide is also a factor, with BN dominating the semi-urban and rural constituencies.

Muda could win Puteri Wangsa mainly due to the over 60% of non-Malay population within this urban state constituency. With a slightly higher non-Malay population in semi-urban state seats such as Bukit Batu, PKR managed to secure only this one for the party in the election.

With merely 53.6% of overall voter turnout during this Johor state election, potentially there could well be only 14% of young Johoreans under 30 (approximately 103,732 out of 740,945) who cast their votes.

According to the Election Commission (EC), 28.53% out of 2,597,742 eligible Johorean voters are under 30 years old; 173,177 Johoreans (6.67%) are between 18-20 years old; and 567,768 voters (21.86%) are between 21 and 29 years old.

Some NGOs such as Undi Johor and the Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall Youth assisted voters living outside of Johor to fulfil their democratic duty and vote in the Johor state election. However, the outreach efforts were limited – either some Johoreans (including those staying in the city centre of Johor Bahru) were not aware of their eligibility to vote or had no clue about the voting process.

In addition, many young Johoreans do not have a clear and distinct idea of the ideologies of the various parties, what concrete or fleshed-out policies they will bring to the table, and what initiatives they intend to implement to help young Johoreans overcome their economic woes.

Moreover, some young Johoreans working or studying in other states or countries either chose not to go home to cast their votes on polling day or did not arrange postal voting before the deadline on Feb 18. Rising Covid-19 cases during recent weeks and financial barriers to travelling back to their respective home town constituencies were among the factors that deterred them from voting.

As a result, only 7,824 Malaysians overseas registered as postal voters for the Johor state election. Some state constituencies near Singapore like Puteri Wangsa, Johor Jaya and Kota Iskandar (see Table 3) recorded the lowest voter turnout at 46.94%, 51.58% and 48.72% respectively.

Therefore, to increase awareness about the importance of voting among eligible young voters under 30 nationwide, the EC could take the lead to educate urban and rural Malaysian youths on why votes matter by conducting roadshows, seminars and workshops.

Although Undi 18 – as a Malaysian youth movement – advocated for the amendment of Article 119(1) of the Federal Constitution to reduce the minimum voting age in Malaysia from 21 to 18, many of the youths residing outside of the Klang Valley are oblivious to the current political climate in the country. They are unaware of how their votes could influence policymaking and the impact on the next generation(s) to come.

In a nutshell, the government, political parties and civil societies have to think of creative ways to encourage, educate and mobilise more young voters under 30 to come out and vote in the subsequent elections, especially in relation to the soon-to-be-held 15th general election. Continuous efforts in spurring the young to be involved in the democratic process would motivate them to vote for a better future for Malaysia.

Amanda Yeo is a research analyst at independent think tank Emir Research.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of MalaysiaNow.

Subscribe to our newsletter

To be updated with all the latest news and analyses daily.